Rate Setting and Regulating is Hard

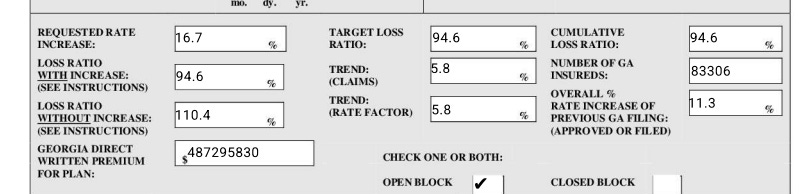

After my post yesterday, a few folks reached out to me and suggested I may be wrong on why Kaiser is being suppressed. I alluded to the possibility of network capacity being one of the reasons, but I focused on the financial losses. I think it may be a combination of the two. In Kaiser’s own rate filings, they project a loss ratio of 94.6% which means they were planning on a loss in 2026.

Their actuarial memo also references a capital contribution:

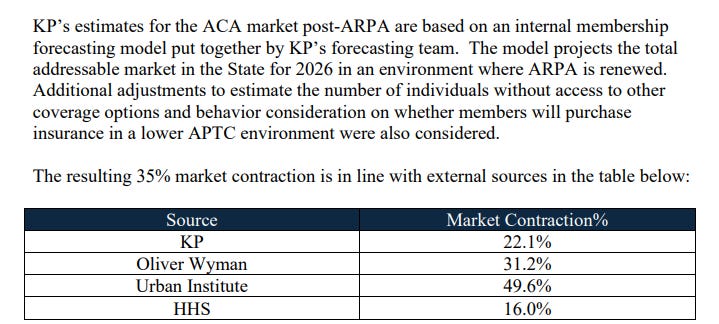

All of this suggests that losses alone were not the sole driver of their decision. However, I suspect the number of members they were getting definitely became a concern - that same actuarial memo showed they expected the market to contract by 35%

If the CMS OEP Snapshot report is any indication, a 35% contraction in the market is likely not to materialize. Their rate filing projected 693,000 member months for 2026, which implies a meaningful decrease in membership from 2025, where just through third quarter, they had 700,000 member months.

Either way, I do think it’s correct to say that they have a lot more membership than they expected. Even if the financial losses are something they can bear, they may still be suffering from the winner’s curse, but in this case, the curse is that they don’t have enough physicians to support a growing membership.1

This is all speculative, of course; I’m not privy to any conversations or documents that I haven’t posted here. But it points to the complexity of the rate filing process and all the many moving pieces. So with that in mind, I thought it would be helpful to walk through how rate setting and the regulation of those rates happens, and why it’s such a challenging thing to do.

Neither Excessive Nor Deficient

I am not an actuary. I have masters’ degrees in divinity and business administration, neither of which make me qualified to opine on whether somebody’s rates are accurate. But I’ve been involved in the process in different ways to know a bit about how the sausage is made.

The goal of any rate-setting process for an insurance company (regardless of what kind of insurance it is) is to set rates that are neither excessive, nor deficient. Excessive rates both harm the buyers of that insurance and, assuming you don’t have a monopoly, probably hurt the insurance company itself because they lose market share. Most people tend to think about the problem of excessive rates: if an insurance company raises rates by a large percentage, there’s often an uproar, demands for the insurance commissioner to do something about it, etc.

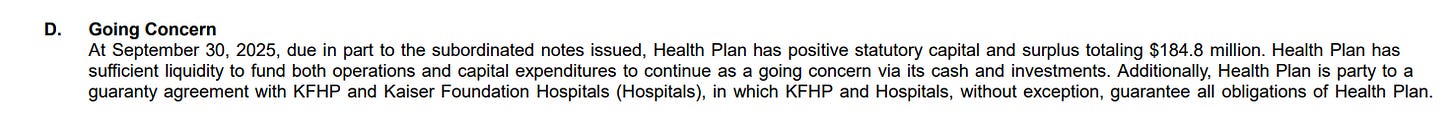

But the problem of deficient rates is actually, in my opinion, a bigger risk. Excessive rates tend to correct themselves: consumers don’t buy the product, or if the carrier is the only option, a competitor will see the big, juicy margins and come in and undercut them over time. Plus, in the health insurance market, margins are regulated by the Medical Loss Ratio rule, so if a carrier’s rates are excessive, they’ll have to rebate the excess margin back to their consumers.2 Assuming a robust and competitive market,3 if a carrier overshoots rates, they’ll correct it in time. But if rates are deficient, it may be impossible to fix before catastrophe strikes. If my assertions in yesterday’s post are correct and Kaiser is suffering the winner’s curse financially, it’s unpleasant for them because they have to contribute capital into the Kaiser Georgia subsidiary, but it’s not a catastrophe (see this note in their third quarter financial statement).

If they had to contribute more capital, they can do so. According to their latest 990, the Kaiser Foundation Health Plan parent company has $9.3B in net assets, and the Kaiser Foundation Hospitals has $46B in net assets, so there’s more than enough to cover $100M in losses if need be. So, to be clear to anyone reading this: Kaiser of Georgia isn’t in any danger of going under. If you are enrolled in a Kaiser of Georgia plan, do not worry.

However, not every insurance carrier has immediate access to capital if their rates are insufficient. Some may not have a well-capitalized parent. Some may have a well-capitalized parent, but the subsidiary that’s selling the coverage may not have a guaranty agreement. If the carrier underpriced, they can end up failing - and if that happens mid-year (as happened with some of the Friday subsidiaries a few years ago, and happened with some of the Co-ops at the beginning of the ACA), it’s hugely disruptive for members. State guaranty associations step in, but it’s limited to usually between $300,000 and $500,000 worth of claims per member - which a transplant or a high cost drug can easily exceed. You also may have to switch plans mid-year, and your new health plan probably won’t honor the deductible you met while enrolled with a competitor who failed. You’ll have to get a whole new set of prior authorizations. The network won’t be the same. It’s a hugely disruptive mess.

But regulators have a really hard job. Insurance Commissioners at the state level are typically either elected statewide, or appointed by the governor. Either way, it’s an inherently political role. No one is going to win an election for insurance commissioner on the platform of “I’m going to make those bastards at the insurance companies raise rates higher to avoid solvency risk.” There’s lots of incentives to try to push rates lower, and not much to try to push rates higher. No one is going to remember the insurance commissioner who prevented a catastrophe by quietly forcing a carrier to raise rates. I don’t envy the task. There’s a lot of assumptions that go into a rate filing, and many of them are interdependent on things happening not just within that carrier, but within the market as well. Regulators and carriers can have different incentives, and the inherent information asymmetries make it very tough for anyone to know what to believe.

Actuarial Memos and Objections

In the ACA market, carriers have to file a lot of different documents and templates - some are standardized at the federal level, and then each state has their own set of requirements. Most of the federal templates are more around things like plan design, formulary, network, URLs, etc. - the sorts of things that affect how a plan is going to look like to a consumer buying on HealthCare.gov or the state exchange.

Then, there’s the Unified Rate Review Template (URRT). This has information about the health plan’s claims experience in the prior year, how they expect it to look like in the year they’re filing for, and then how that is going to get distributed among each plan they’re selling.

Along with the URRT, plans have to file an actuarial memo - this memo provides details about the assumptions that are in the URRT and how they came up with them. In some states, only the redacted version becomes public, and carriers have gotten more and more aggressive with how much they redact the memos over time to where if it’s a redacted version, you should not expect to get any useful information out of it.

But some states don’t allow redactions, and others release unredacted versions after the rate filing season is over. You can then use this to get a feel for why a carrier may have done something. But there’s a big caveat here: carriers have incentives to tell regulators a particular story, and it may not be the most plausible one or one they necessarily believe. They also know that parts of it may become public and don’t want to reveal things to their competitors.

For example, a carrier may have investors or owners who want to prioritize growth over profit. This isn’t necessarily an unreasonable strategy in the right circumstances, but unprofitable growth requires a lot of capital.4 And so a carrier may underprice but not want to reveal the extent of the underpricing to the regulator. The assumptions built into the rates can include things like what provider contracts a carrier has or expects to have. If a carrier has negotiated a lower priced contract, they’ll include that as an input to their rate filing. But provider contracts are complicated, and states probably don’t have the resources to analyze all the assumptions that went into how a carrier thinks a better contract will affect their rates.

Then there’s the even harder to quantify assumptions like market morbidity. If one carrier thinks the market is going to get a lot sicker than another, a regulator might try to force everyone to converge on a similar number to avoid the winners curse risk. But this requires a lot of coordination, and sharing too much between competitors can get dangerously close to enabling collusion.

All of this is hard in the best of times… and this year was complicated with lots of moving pieces, with many carriers doing 3 or 4 revisions of their rate filings as policy changes and market conditions shifted.

If you found this interesting, subscribe or leave a comment. And let me know what you want to learn about next!

Kaiser doesn’t own any hospitals in Georgia so capacity constraints would primarily be around their physician practices.

For now I’m ignoring many of the valid criticisms of the structure of the MLR rules such as when a carrier owns the providers and how margin can be shifted between them to meet the letter of the MLR rule while preserving lots of internal margin within another subsidiary.

This is, I admit, a big assumption. Health insurance has rather large barriers to entry, and those barriers are even larger for markets like the ACA where both state and federal regulations intersect and create lots of complexity, and it’s not a given that a market will be competitive. But for now… move past it and accept the premise.

A future post will look at risk based capital and how it causes a double whammy if you’re growing and losing a lot of money.